Play to the Whistle

Walk out onto any football practice field, and eventually in the practice you’ll hear a coach scream, “What are you doing??? Don’t stop until the whistle blows, Neff!” Playing to the whistle is emblematic of exerting maximum effort and not giving up, even if you think you are out of the play. Rallying to the football to make sure the play was complete is important.

As a coach, I am no different than any other. I can excuse active mistakes – even over-eager ones – but what I can’t countenance is laziness and poor effort. If you’re going to make a mistake, make it going 100 mph. Effort mistakes are far more forgivable than lazy ones.

As a player, I prided myself of always hustling to get to the ball and never giving up on a play. In fact, I probably built a semi-successful college football career on that principle. Always running to the ball. I (too frequently) crow that I am 2nd in the Davidson College sports record book (Yes, Stephen Curry and I are both in that book! Lol) for career fumble recoveries. This is fairly emblematic of who I was. It doesn’t take any real skill to recover a fumble. Sometimes, it appears that it can just be chalked up to luck. But I don’t believe that. I think you create opportunity with effort, and there were a number of times where my effort to get to the ball and the ballcarrier meant that I was in a position to make a play … like a fumble recovery.

But like anything else, that effort can be taken too far if it violates important rules or principles. Extracurricular activity after the whistle in football will earn a penalty flag from referees – often the worst kind. 15-yard penalties are drive killers if the offense is penalized and oxygen for an offense if the defense is penalized.

Similarly, lawyers questioning witnesses in court should play all the way through and get as many good things from the witness as we can. But just like in football, there’s a time to stop. Going past that point will get us penalized.

Let’s look at good and bad examples of playing to the whistle versus playing after the whistle.

2015: Chattanooga Christian School vs. Dekalb County (TN): I was coaching defensive backs for CCS in a rare playoff game. Indeed, this would become, I believe, the first playoff win in school history. One of my defensive backs was Will Patton, who was a fantastic all-around athlete. He played safety and corner on defense, wide receiver on offense, and was also our punter. Apparently, he was an excellent soccer player also. I wouldn’t know; I don’t watch soccer!

In this game, he was playing cornerback and the play went to the opposite side from him. The running back broke through and had open field down the sidelines for an easy 70-yard touchdown run.

Until he didn’t.

All of a sudden, I saw Will sprinting at top speed from across the field and then directly behind the runner, chasing him even though the effort seemed to be futile. The running back appeared to be throttling down a bit as he approached the end zone, not expecting to get caught from behind.

But Will got to him and dragged him down on the 5. From there, incredibly, our defense held. That effort saved seven points … and the game. That’s winning football. That’s playing to the whistle.

I wish I could find a video of that somewhere…

I researched his old Hudl account, hoping I would find it there. His “senior highlight” film was 3 minutes long (and should have been much longer), and doesn’t include that play, which is a shame. I blame myself; if I were thinking about it, I would have told him to put that play pinned to the top of his highlights. And if I were a college coach looking at his tape, I would have offered him a scholarship based on that play alone.

2020: Seattle Seahawks at Arizona Cardinals: Seahawks wide receiver D.K. Metcalf is a physical marvel. At 6’4”, 235 lbs, he is far larger than most wide receivers. And he runs a blistering 4.3 40-yard dash. Elite speed. Elite size. Unfair for a wide receiver to be that big and fast.

In the 2nd quarter, the Seahawks were driving for a touchdown deep in Cardinals territory, but All Pro safety Budda Baker intercepted a pass at the 3 yard line and had a clear path to the end zone 97 yards away. In fact, if you watch the video, there didn’t appear to be anyone in the picture who would have had even the slightest opportunity to catch Baker, who ran a 4.45 40 himself – not slow at all. In fact, 4.45 is great speed (and I’m not just saying that because I ran a 4.5 in 1986…).

All of a sudden, out of nowhere, Metcalf appeared on the screen chasing Baker directly from behind. He caught up to him just short of the Seahawks’ goal line. The Seattle defense then held for four downs, and the Cardinals did not score. Seven points saved.

The metrics on the play revealed that Metcalf ran 22.64 mph (in pads, mind you) and covered 114.8 yards to catch Baker and make the tackle. Baker, for his part, hit a top speed of 21.27 mph – not too shabby.

Play to the whistle.

1987: Davidson vs Wingate. But don’t play past the whistle! In college, as I said, I always played hard and ran to the ball. On one particular play, however, I went too far. Having chased the runner from all the way on the other side of the field, I got there just a little late and shoved him after he was out of bounds.

You could see on the film when the referee threw his flag and penalized me. In my defense, our field was lined so that there was a 2nd white parallel line painted several yards outside the sidelines. I had run so far and was so focused on him that I thought that 2nd line was the sideline, and that’s why I shoved him then. I thought he was still in bounds. But the whistle had blown…

Don’t play past the whistle.

1999: United States v. Seay/Shelton: In two of my final trials as an active-duty Army Captain, I was prosecuting the courts-martial of Bobby Seay and Darrell Shelton. In 1997, Seay helped Shelton murder a fellow soldier. As the victim was being stabbed, he looked at Seay and said, “What have I ever done to you, Bo?” Seay leaned into him and responded, “Ask the Lord for forgiveness” before killing him. They dumped his body in a remote section of the Air Force Academy where it was not discovered for many months.

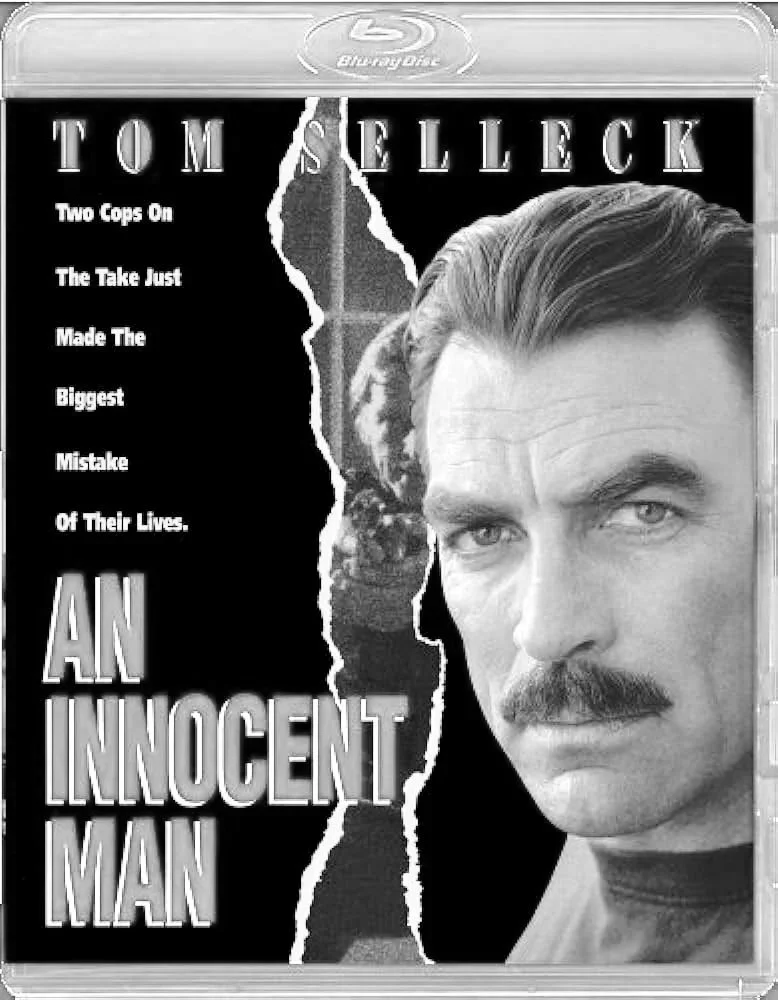

Seay later confessed to his wife while they watched a movie, “An Innocent Man,” starring Tom Selleck. His wife testified at trial about her observations the night of the murder when the victim was at their house, but she was not permitted to testify about Seay’s confession. It was protected by spousal communication privilege.

During her cross-examination, however, the defense lawyer “went past the whistle” and asked one question too many when he said, “Isn’t true Mrs. Seay, that you don’t have ANY direct information that my client committed this murder?”

Oops. He went TOO far past the point where he should have stopped, and he opened the door for admission of Seay’s confession. I immediately asked for a 39a session[1] and requested that the judge either allow Mrs. Seay to fully answer the question or permit me to ask her that question on redirect exam. After all, the complete truthful answer to the question was that she did have direct information that her husband had committed the murder – he had told her so!

Don’t play past the whistle.

The judge, Colonel Parrish, was an outstanding judge. He looked at me, grinned, and said, “Captain Neff, you are correct. The defense has gone too far and opened the door. But I’m not letting you walk through it.” He “picked up the flag”[2] and did not penalize the defense for the mistake. I believe he was wise enough to know we had presented a powerful case and did not want to create an unnecessary appellate issue. Seay was convicted, and his appeal was denied by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces.

[1] In the Uniform Code of Military Justice, a 39a session is the equivalent of a sidebar in a civilian trial where the judge listens to legal arguments from the lawyers outside the hearing of the jury. In the military, a 39a session results in the panel (jury) leaving the courtroom, so I tried to ask for those as sparingly as possible lest the members of the panel get upset.

[2] In football, referees will sometimes pick up their flags and decide not to call a penalty they originally intended to call.